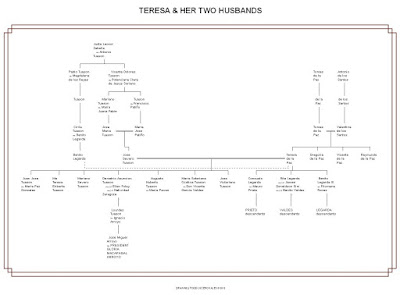

Probably due to our masculine culture, majority of Filipino genealogies almost always come from the father's side of the family. Since today, March 8, is the International Women's Day, I find it fitting to write a brief narrative about the family of Teresa de la Paz Tuason Legarda. Her descedants are unique (or one of the unique ones) because their kinship is based on the female, rather than the male, line. The Tuason-Legarda-Prieto-Valdes clan identifies itself with this very small but strong lady.

Her descendants jokingly call her a woman who was a cougar even before the word was popular. Many of her relatives during her lifetime viewed her with utmost respect and awe, sometimes bordering on worship. She was indeed a woman who, despite not being the first choice of her first husband's aristocratic family, managed an immense fortune and imbued great strength and character, both of which have passed down to her numerous descendants. Her descendants today, roughly numbering 800 or so, meet every five years to celebrate and renew their kinship.

Teresa's full name after her two marriages, in the Spanish style, would be Doña Teresa de la Paz y de los Santos vda. de Tuason de Legarda. She was born on October 15, 1841, in what is now modern-day Marikina. Historian Luciano R. Santiago wrote in his scholarly article on Teresa that she was the daughter of Don Tomas de la Cruz and Doña Valentina de los Santos. Although her family was classified as mestizo sangley (Chinese) and her father was even at one point the gobernadorcillo for the mestizo Chinese population of Marikina, it is clear from her parents' last names that their Chinese ancestry was already diluted. The choice of their last names is also a possible evidence of further dilution; clearly, though many of the Chinese population were baptized into the Catholic faith and tried assimilation into mainstream society, many of these Chino Cristianos (Chinese Christians) held on to their sangley heritage by Hispanizing (or could also be seen as Filipinizing) their chinese last names. Thus, those who stubbornly and proudly clung to their Chinese heritage despite having been baptized Christians had surnames such as Tuason, Lacson, Syquia, Angco, and so on.

Still, Teresa's family was prominent enough and both sides of her family held the post of gobernadorcillo for quite some time. She soon caught the eye of the heir to the Tuason fortune, Don Jose Severo Tuason, the son of Don Jose Maria Tuason and Doña Maria Jose Patiño y Tuason (they were first cousins). The Tuasons, it must be said here, were the nearest thing to Spanish nobility in the Philippines at that time. Historically, they were the only Chinese family in the Philippines granted with patents of nobility by a Spanish monarch. As such, the entire aristocratic Tuason clan expected Don Jose Severo to marry at least a cousin or another "aristocratic" woman.

The real reason to the family's initial opposition to their union was probably due to the fact that the de la Paz and de los Santos families, being tenants of the Tuason hacienda, had a long history of opposing the rent imposed by the Tuason hacienderos, going as far back to Teresa's great-grandparents. Still, the Jose Severo and Teresa union pushed through. And family lore suggests that soon most of Don Jose Severo's relatives accepted Teresa as a fitting consort for the Tuason heir, considering she had acumen for business and was also well-versed in the arts and educational pursuits. And by a stroke of luck, she was able to produce as her firstborn a son, Don Jose Victoriano, thus ensuring the continuation of the Tuason hacienda.

Their marriage, short though it was, seemed to have been happy. By all accounts Teresa proved to be the model wife and mother, and she gave birth to five sons and two daughters. Jose Severo's will stipulated that Teresa and a brother-in-law, Don Gonzalo Tuason, would co-manage and execute Jose Severo's vast properties. A further clause was added, however. In the event of Teresa's remarriage, she would lose all her rights to govern her children's finances.

Naturally, for a very strong-willed woman like Teresa, widowhood was not at all fun. Because she was still young she set her eyes on another Tuason, Don Benito Legarda y Tuason, a third cousin of Jose Severo. A year and two months after Jose Severo's death, and just right after Benito finished law school. Teresa married Don Benito, who was twelve years younger than she was. Their marriage was also a happy one and produced three children. Throughout the remainder of her life, she fought quite a number of lawsuits against her. However, she managed to enlarge her properties and hold on to the Tuason estates, which once more came under her guardianship upon her eldest son's untimely demise. She herself died in 1890 at the age of 48 years old due to pneumonia.

It is said that empires can only be held by the strong, and this was true of the Tuason's vast estates. Soon after Teresa's death heaps upon heaps of lawsuits were filed against the Tuason estate for various reasons. Though the romanticized and sanitized version of the family history is well known, what was not common knowledge was the sordid details that followed Teresa's death. Soon after her death, Don Benito, Teresa's widower, tried to marry Teresa Eriberta Tuason, his own stepdaughter. This did not come to fruition, however.

Truly, Teresa was obviously the glue that held everything together. With her death, coupled with the shift from Spanish to American rule, the vast Tuason empire collapsed bit by bit.

Of course, her descendants are still very, very well off compared to other families. The names Tuason, Prieto, Legarda, and Valdes are still at the top of Manila society to this very day. And, what's even better, Teresa's progeny have diversified their skills and influence and are found in the arts, the media, politics, business, and real estate. Prominent descendants of Teresa include former first gentleman Jose Miguel Tuason Arroyo, husband of former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and their children; and Tessie Prieto Valdes, among others.

___________________________________________________________________________

Sources:

1. Luciano P.R. Santiago. The Last Haciendera: Teresa de la Paz. Philippines Studies vol.46 no.3. Manila: Ateneo de Manila University, 1998.

2. Tessa Prieto-Valdes. Presenting Teresa de la Paz y de los Santos’ descendants- all 800 of us, The Philippine Daily Inquirer. Manila: PDI Publishing, 2010.

3. Alfred W. McCoy. Policing America's Empire. WI: University of Wisonsin Press, 2002.

4. Supreme Court decision: Collector of Internal Revenue vs. Antonio Prieto et. al.

No comments:

Post a Comment