Former Commonwealth President Sergio Osmeña’s paternity has always been shrouded in mystery. While he lived, he never spoke about his father. Because all his children have already passed on, his grandchildren are the closest living descendants who can shed light on this mystery. Unfortunately, he refused to mention if he knew his father, but he also never supposedly spoke of this matter with his children or grandchildren.

An oral history that tells us more about the attitude of Sergio Osmeña towards the topic of his paternity is in an interview by American historian Michael Cullinane with the late Senator John “Sonny” Osmeña. Sonny Osmeña informed Cullinane in the 70s that as a small boy he asked Sergio who his father was. In response, Sergio supposedly gave him a gentle slap on the cheek and told him to never ask him that question again. As such, Sonny claimed that he had no idea who Sergio’s father was. However, in another interview in the 1980s with Jesusa Sanson Zamora, it was revealed that Sonny Osmeña told her that in his final years, Don Sergio wanted to gather his family to tell them that his father was Antonio Sanson. Sergio’s second wife, Esperanza, however, ordered that this should not be made public. So, Sergio went to his grave never revealing his father’s name.

For decades now, DNA testing has been used to solve centuries-old mysteries. For instance, in 2012 the remains of England’s King Richard III were thought to have been discovered but in order to confirm that the skeleton belonged to the said ruler, researchers turned to genetic genealogy methods. A comparison was made to Richard’s mitochondrial DNA with those of two living cousins. Their mitochondrial DNA turned out to match the remains, supporting previously accumulated evidence indicating King Richard III's remains had been discovered. Another mystery solved by genetics were those of the Romanov bodies. In 1991, to prove that the bones in Yekaterinburg were indeed those of the last Russian Imperial family, Prince Philip, husband of Queen Elizabeth II, donated his mitochondrial DNA for comparison with the bones found and it was conclusively proven that Prince Philip’s mitochondrial DNA matched those of the bodies found. These and many other examples show how DNA testing is used to help solve what used to be believed as impossible historical mysteries.

Historical Context

While the DNA result is conclusive, a short discussion of what has been written and said about the paternity of Sergio Osmeña is needed. It must be understood that while the internet today is full of newspaper and journal articles as well as book references and blog posts that discuss the alleged fathers of Don Sergio Osmeña, the earliest biographies and write-ups on Osmeña, especially during his lifetime, did not at all mention the name of either Don Antonio Sanson or Don Pedro Gotiaoco as the possible father of Osmeña. Most of these early biographies were silent about his parentage most of the time. For instance, in a 1931 collection of biographies of prominent Filipinos, neither Sergio’s father nor mother was mentioned in his biographical sketch. A US magazine’s feature article on Don Sergio in 1944 indicates that “Osmeña, who recently became the second president of the Philippine Commonwealth…refuses to discuss his father or mother or his early home life”. Even books after Don Sergio’s death in 1961 were still mostly silent on his father’s identity, one in 1967 simply skating over his early years without mentioning a mother or alleged father and another in 1976 saying “it was Juana Osmeña y Suico who was the mother of Sergio Osmeña; the father was unknown”.

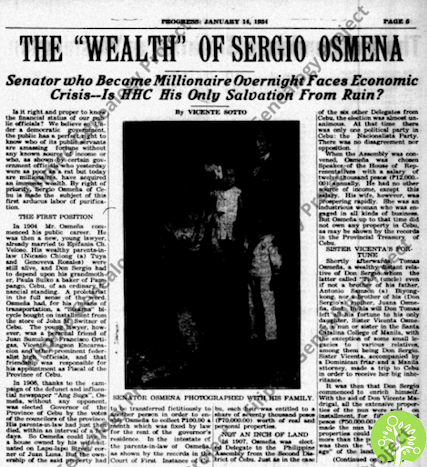

Despite all the mystery surrounding his father’s identity, two names did come out as his possible fathers. The first, and the earliest name to be associated with Osmeña, was Don Antonio Sanson of the prominent Sanson clan of Parian. He was briefly mentioned in a Progress newspaper article written by Vicente Sotto in 1934 as the father of Osmeña. Being the political rival of Osmeña, Sotto probably wanted to humiliate Osmeña by mentioning Sanson since he was much older than Juana Osmeña and was already married with at least one child. In 1961, a monograph mentioned that “the most convincing evidence to date suggests that his (Osmeña’s) father was a prominent and wealthy man from the city of Cebu who owned extensive land holdings in the northeastern municipality of Borbon named Antonio Sanson. Since Sanson was already a married man, it was not possible for him to establish a legitimate bond with Osmeña’s mother.” The name of Sanson being Osmeña’s father, for some reason, started to be mentioned less and less especially after Osmeña’s death in 1961, and another name, Pedro Singson Gotiaoco, became the more accepted identity of Sergio’s father.

An early mention of Don Pedro Gotiaoco being Don Sergio’s father was in the 1992 “She-wu Hua-shang Ching-ying”, a Chinese version of Forbes magazine, which indicated that “Gotiaoco’s second wife is said to be the mother of one of the country’s most honored senior politicians, Sergio Osmena, Sr... While there are expressed doubts regarding the authenticity of Osmena’s biological relations to Gotiaoco, there is no evidence available to prove the contrary. The 10th volume of a collection of Jinjiang historical documents published by the Fujian Political Association, however, indicates that Sergio Osmena’s Chinese name is given as Go Si Bin.” This is interesting because the supposed Chinese name of Sergio Osmeña indicated him as a fourth son (si) which tallies with the known fact that Pedro Gotiaoco had three sons with his Chinese wife.

Over the years, more and more articles have been written supporting the Gotiaoco paternity rather than Sanson’s, and in fact, President Osmeña’s official Wikipedia entry indicates that his father was Gotiaoco, and his master profile on the online genealogy site Geni.com also indicates that Gotiaoco was his father. One of the country’s leading Chinese writers and social historians, Wilson Lee Flores, wrote in 2010 that “the father of the late incorruptible and good President Sergio Osmeña, Sr. was the 19th-century rags-to-riches Chinese immigrant tycoon, philanthropist, and Cebu Chinese community leader Don Pedro Lee Gotiaoco”. Some circumstantial evidence provided in support of Gotiaoco’s paternity, as discussed in National Artist for Literature Dr. Resil B. Mojares’s Book of Go: The Gotiaoco-Gotianuy-Go Family of Cebu, included the lore that “Pedro Gotiaoco and Juana Osmeña knew each other since they lived in the same block”, “Juana used to buy oil and matches from Pedro; Pedro patronized the bakery and gaming parlor Juana's mother, Paula Suico, operated out of their home”, “Pedro and Juana were often seen going out on paseos”, and that Gotiaoco helped pay for Sergio Osmeña's education at Seminario-Colegio de San Carlos and Universidad de Santo Tomas.”

Despite all the articles about Gotiaoco being Don Sergio’s more probable father, American historian Michael Cullinane, who has been studying primary documents from Cebu as well as other documents and sources, and who has conducted countless interviews with members of Cebu’s old families, insists that Antonio Sanson was the more logical candidate as Don Sergio’s father. As cited by John T. Sidel in his 1995 book, “Cullinane, in published writings and personal communications with the author, expressed doubt about the veracity of these claims (that Gotiaoco was Don Sergio’s father), noting evidence that suggests that the real father of Sergio Osmeña Sr. was another Chinese merchant, and that the putative kinship ties between the Osmeñas and Gotiaocos were convenient bases for a long-lasting business-cum-political alliance between the families.” Cullinane in 1999 offered both the names of Gotiaoco and Sanson as possible fathers of Osmeña; in the body of the book Cullinane mentioned that Don Sergio took refuge in Borbon, one of Cebu’s northern towns on the east coast, where his alleged father, Antonio Sanson, had lived. He further conclusively wrote in 2015 that Sergio Osmeña was the illegitimate son of Antonio Sanson and in his 2022 The Chinese Mestizos of Cebu City (1750–1900), he placed Antonio Sanson’s name as Sergio’s father in the family tree illustration at the end of the book.

DNA Testing and Sergio Osmeña’s True Father

Annie Osmeña Aboitiz and Marilou Enriquez Bernardo, a granddaughter and great-granddaughter of Sergio Osmeña, commissioned a DNA test in 2023 to finally have a definitive answer to Osmeña’s paternity. Using the company EasyDNA, a Y-Chromosome test was utilized to determine Osmeña’s paternity. The Y chromosome test is used to explore ancestry in the direct male line, and only individuals with a Y chromosome (males) can have this type of testing done. The Y-DNA test, otherwise called the Y chromosome DNA test, is a male-specific genealogical DNA test used for exploring a man’s patrilineal or direct father’s-line ancestry. What this means to prove the paternity of Don Sergio Osmeña is this: if we can compare the Y-DNA of a direct male-line descendant of Don Sergio with the Y-DNA of direct male-line descendants of both the Gotiaoco and Sanson families, then we will finally have scientific and definitive proof of who Don Sergio’s father was.

Both the donors for the Osmeña and Gotiaoco DNA are grandsons of our main subjects Sergio Osmeña, Sr., and his alleged father #1, Don Pedro Gotiaoco. Unfortunately for the Sanson DNA, while Don Antonio Sanson was known to have at least three wives, he only had one child, a daughter. However, as long as the sample comes from the same paternal lineage, such as any male-line direct descendant of Don Antonio Sanson’s brothers or male cousins, then this sample could still be used to compare against the Osmeña DNA. Because we do not know of any male siblings of Don Antonio Sanson, we went up one generation higher to Don Antonio Sanson’s father’s brother, Ambrosio Climaco de Sanson, whose direct male-line descendant, Ronnie Sanson, gave his DNA.

Result 1: Y-STR Comparison Report between Osmeña and Gotiaoco DNA

Result 2: Y-STR Comparison Report between Osmeña and Sanson DNA

The fact that all 23 Y-STRs of the Osmeña DNA matched the 23 Y-STRs of the Sanson DNA conclusively proves a shared descent from the same male line. And since one of Sergio Osmeña’s alleged fathers was Don Antonio Sanson, we can now safely and scientifically conclude, supported by historical documents and various oral histories, that the true father of President Sergio Osmeña was Don Antonio Sanson.

Watch the 3-part video of the full revelation of President Osmena's true father: